What's in a Linux System? (Part 2)

After a long hiatus, this is part two of my series on the pieces of a Linux system and how they fit together. It took me a while to decide how I wanted to lay out this section and the next, but I'm fairly happy with what I have now.

Userland

In addition to the Linux kernel, there are a number of programs that are expected to be present in a Linux system. Some are daemons (programs that run in the background and provide services), while others interact with the user directly.

The Init Daemon

The init daemon is the most important daemon on the system. Its job is primarily to manage other daemons (although a few other jobs have been tacked on in recent times). The kernel starts the init daemon during boot, and if the init daemon ever stops running, the kernel brings the entire system screeching to a halt as a precautionary measure. There are several different init daemons available, including the venerable old sysvinit (descended from the init daemon used in Unix System V, hence the name), Upstart, a more recent init daemon most closely associated with Ubuntu Linux, and systemd, an init daemon with some rather ambitious goals used in Fedora and Arch Linux.

The main difference between the various init daemons is how they decide when and how to start the various other daemons. For example, sysvinit uses a rather simplistic system based on sort order. Essentially, the startup and shutdown scripts for the various daemons are named such that if daemon A needs to start before daemon B, then the name of daemon A's startup script comes before the name of daemon B's startup script alphabetically. Prefixes like S01 and K01 (S for "start" and K for "kill") are typically used to force the proper order regardless of the actual names of the daemons. Upstart, on the other hand, has configuration files in place of scripts, and these configuration files specify dependencies. Thus, if daemon B is configured as depending on daemon A, then Upstart will start daemon A before starting daemon B. systemd, on the other hand, recognizes that dependencies almost always involve one daemon creating a communications socket and another one talking to it through that socket, so it creates these sockets itself and then starts everything all at once, handing off the sockets to the appropriate programs as they load. While this may cause delays in communication, daemons can typically tolerate such delays because sockets were designed for network communication, which is inherently slow (at least by computer standards).

Upstart and systemd also provide a service that sysvinit doesn't: supervision. sysvinit doesn't "know" when one of the daemons it launched stops running. Upstart and systemd do, and they can be configured to automatically restart a daemon that has stopped unexpectedly. systemd takes it a step further, using features of the Linux kernel (cgroups) to track not just daemons, but programs started by the daemons, too. Thus, a daemon that tries to escape supervision by repeatedly launching a copy of itself and then exiting can't get away, and a daemon that runs multiple child daemons will have all of its children managed along with it.

Standard Utilities

There are a number of standard command-line utilities that are generally expected to be present on a Linux system. Most of these programs are also present on other Unix-family operating systems, such as the BSDs and Solaris. Here are a few of them:

-

ls: lists files in a directory -

cp: copies a file or directory -

mv: moves a file or directory -

ln: creates links (file-like objects that "point" to other files or directories) -

chmod: changes file and directory access permissions (a.k.a. mode, hence the name) -

chown: changes file and directory ownership -

sed: finds and replaces text on a line-by-line basis -

awk: extremely flexible text manipulation program (uses a programming language also called awk) -

grep: searches for regular expressions (imagine a word processor's "find" interface on steroids) -

ps: lists running programs and information about them (e.g. RAM usage, time spent actively running) -

find: finds files according to various criteria (e.g. name, type (file or directory), size)

There are two major implementations of the standard command-line utilities: GNU and BSD. The GNU utilities came from GNU, a project to recreate Unix under a free software license, while the BSD utilities came from the version of Unix distributed by UC Berkeley. The two are mostly identical from a user's perspective, but there are a few annoying differences. For example, GNU ps will accept BSD-style options, but BSD ps will not accept GNU-style options, and GNU find will start its search in the current directory if no directory is specified, but BSD find will spit out an error and terminate.

Utilities for configuring the system (e.g. manually setting a network interface's IP address) are more likely to differ between the various Unix-type systems, and they can even differ between Linux distributions. For example, ifconfig has traditionally been used for network interface configuration on Linux and other Unix-type systems, but the rise of mobile devices has led to the development of management daemons for network interfaces (such as Wicd and NetworkManager), as static configuration with ifconfig can't deal with the frequently-changing environment of a mobile device. Since these daemons may override manual configuration with ifconfig, they typically provide their own interface. NetworkManager, for example, has a number of graphical interfaces designed to integrate with the various desktop environments as well as a command-line client, nmcli. Solaris, one of the Unix systems of old, uses (as of version 11) a utility called netadm instead of ifconfig.

The Shell

The shell is the program that provides the command-line interface. It interprets commands (or entire scripts) typed by the user and performs the actions described by them. Additionally, it provides a number of built-in commands, most notable of which is cd. cd changes the current directory. Many programs (such as ls and find mentioned above) have some mode of operation that operates on the current directory, making cd a very important command. The reason for cd being a built-in instead a separate program is that it needs to change the directory of the currently-running shell, and a program can't change its parent's current directory (at least not without resorting to questionable and brittle hacks).

There are a number of shells in common use, including the venerable sh (the Bourne Shell or something 100% compatible with it), Bash (the Bourne Again Shell), and zsh (a Bash-compatible shell popular among power users). There are some that were once popular, but have largely fallen from favor, such as csh, tcsh, and ksh.

The shell can also run a script, which is a sequence of commands (and control structures, like loops and if statements) that is typically used to automate a relatively simple but extremely tedious task. Some shells, like Bash, provide some built-in commands that override some of the standard programs, often with slightly different options for behavior. This can be problematic from a portability standpoint: sh or a 100% compatible shell is all but guaranteed to be present on any Unix-family system, but Bash is not. Many Bash scripts are also valid sh scripts, but accidentally relying on the behavior of a Bash built-in command that is not present in sh is a common way to accidentally write an incompatible script. In fact, accidentally relying on Bash-specific behavior is so common that such quirks have their own name: Bashisms.

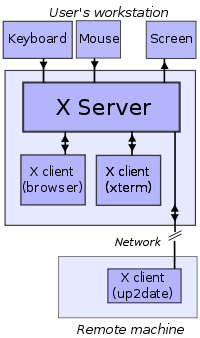

The Text Editor

Any serious Linux or Unix user expects the system to have some kind of text editor that works at least in text-only console mode, if not graphical mode. Which one is the "correct" one has been a point of contention for decades. Some form of vi is almost always available, although Ubuntu Linux systems tend to promote the more user-friendly nano instead. Power users tend to favor vi or Emacs, which both have a wide array of extremely powerful featues and a rather steep learning curve. The oldest of the Unix greybeards (and the masochistic) may prefer ed.

X

(source)

(source)

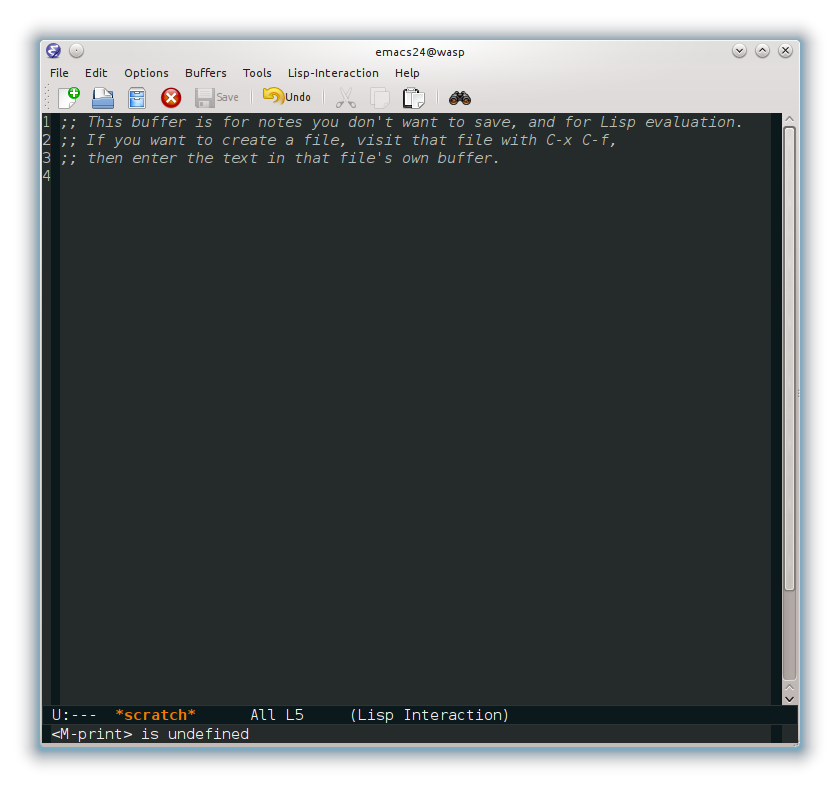

X is a program that lets other programs draw graphics on the screen and receive events (e.g. key press or mouse movement) from input devices like keyboards and mice. It doesn't really have any direct analog on Windows or Mac OS X, although it is possible to run an X server on either one. It's been around for a long time, having started development in the 80's as a graphics system for the Unix operating systems of the day, and it shows. Traditionally, applications would connect to the X server over the network and send drawing commands (e.g. "draw a circle of radius 5 with line thickness 2 centered at position (20, 46)" or "change drawing color to dark red"), which would be carried out by X. This was highly advantageous, as these commands were very small compared to the images they drew. Sending the images themselves over the network at the rate needed for interactive use was impossible or infeasible. Today, the X server and the application almost always run on the same machine, and quite a few applications do their own drawing and send the result to X, either for ease of programming or for performance reasons. In the coming years, X will probably be largely supplanted by Wayland, a modern graphics management system that does little more than manage surfaces for applications to draw on. Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu, has introduced a competitor called Mir. There are some notiable political issues surrounding it, mainly lingering ill-will caused by Canonical spreading incorrect information about Wayland when explaining their decision to develop Mir.

Most programs don't use X directly, since the programming interface X provides is quite primitive. The only real reason to use X directly is to manage X itself (e.g. configuring the use of multiple monitors). Instead, most programs use toolkit libraries like GTK+ and Qt, which are roughly analogous to Win32 on Windows and Cocoa on Mac OS X. The toolkit libraries provide a multitude of convenient building blocks for constructing graphical interfaces (e.g. buttons, dialog boxes, menus). Qt also includes useful non-graphical things like data structures and network communication functions, while GTK+ relies on related but separate libraries like GLib and GObject for those things. The widespread use of toolkits like GTK+ and Qt means that the transition to Wayland (or Mir) will require no work whatsoever for most applications, as the libraries hide such implementation details from the programmer. This flexibility allows many programs written for Linux to run on Windows and Mac OS X as well (e.g. Pidgin, which uses GTK+). Indeed, the ability to run on Windows and Mac OS X was the motivation for developing this flexibility in the first place.

The Display Manager

(source)

(source)

It's hard to talk about display managers without touching on desktop environments, which I haven't gotten to yet, so I will mostly discuss the non-DE aspects here and deal with the rest when I discuss desktop environments.

"Display manager" is a bit of a misnomer these days. It made a lot more sense in the past (for reasons I'm most certainly not going to go into here; read up on the history of the X Window System if you're curious), but "login manager" would probably be more accurate now. The display manager takes a username and password and starts a graphical desktop session if the password is correct. Servers, which often don't have any graphical interface, don't usually have a display manager; they use the more primitive, text-mode program "getty" (look it up if you're curious about it). On systems with only one desktop environment installed (most personal systems), the display manager is chosen to match. For example, GDM "goes with" GNOME and KDM "goes with" KDE, although LightDM (with a GTK+ or Qt-based frontend) is gaining popularity for both. There are also a few less common display managers, like SLiM. These tend to take a minimalist approach, sacrificing features in favor of minimal system resource use.